Legitimization of Status: Flourishing

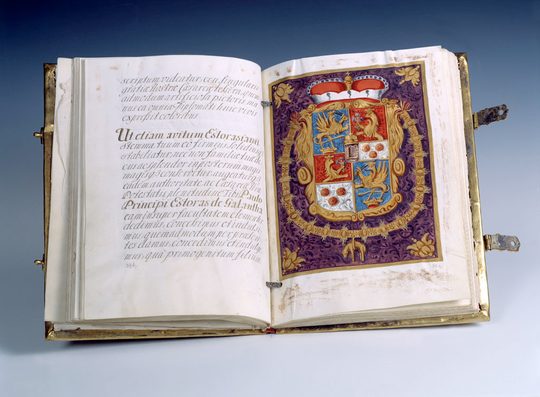

As head of the house, Nikolaus’s son, Prince Paul Esterházy (1635-1713), was able to utilize the material and political prerequisites and develop the art collections in particular. As of 1687 the first Prince Esterházy, Paul consolidated assets and entered early Hungarian Baroque architectural history as sponsor of innumerable church, cloistral, altar and saintly works.

Prince Paul supplemented not only his father’s library with valuable prints from all areas of knowledge and virtually all European countries, with his ‘imagines pretiosae’ he also collected paintings of the contemporary Italian, Dutch and German schools and thus set the cornerstone for the Esterházy painting collection.

As dilettantish ‘uomo universale’, Paul not only undertook alchemical and astronomy studies, he also composed, painted, wrote poetry and Marian homilies. Further, he stood out as an exceptionally gifted dancer of Hungarian folk dances and constructed a still-existing ancestral portrait gallery at Forchtenstein Castle.

In nearly 400 Baroque portraits, the gallery reveals the Esterházy ancestry, which ought to legitimize the rather young family’s claim to Hungarian magnate dynasty. That Paul included nearly all dignitaries of Pannonia as well as the biblical Adam, Noah, Attila the Hun and Count Dracula in his genealogy is a side note in Baroque historiography.

Behind thick walls and locked with complicated mechanisms, Prince Paul constructed a treasure chamber in Forchtenstein Castle starting in 1692 that is now the only remaining Baroque art chamber at its original location in all of Europe.

It reflects a very late emergence of the humanistic idea of collecting, which via the microcosmos—art chamber—portrays and exemplifies the macrocosmos—the world. In size, layout and accoutrements, the Esterházy treasure chamber could easily hold its own against the art and curiosity cabinets in the princely courts of Germany.

With its largely preserved inventory of furnishings and accoutrements, the treasure chamber is unique in Europe and, between its passion for collecting, scholarship and representation of status, presents the ‘princely universe’ of a noble family on the rise in Central Europe.

Several items stand out among its opulent inventory of objects of flora and fauna, ethnography, and art and science from all over the world: the valuable Augsburg machines and clocks, the innumerable lathed artworks made of ivory, curiosities, family heirlooms and booty from the Turkish wars.

The highlight was and remains the collection of silver furniture, which now ranks among the largest of its kind in Europe.

Starting in 1713, the castle no longer served as a place of residence and became first and foremost place of safekeeping for the armoury and arms collections of the Esterházy soldiers. In addition to the Esterházy bodyguards numbering 300 men, a regiment was deployed during times of war due to the social standing of the Esterházy family as princes of the empire.

In addition to the muskets, cuirasses and morions from the 30-Years’ War, the uniforms and booty from Austria’s wars against Prussia and the Napoleonic Wars, magnificent hunting weapons and devices of the Esterházy family are particularly worth mentioning.

The Esterházy arms collections preserved today depict the nearly 300 years of military tradition and are the largest private arms and armour collection in Europe.

The stately economic archive at Forchtenstein, which with its over 12 kilometres of records reveals the family’s large economic influence on possessions in Austria, Hungary and today’s Slovakia and Ukraine, goes back to the early 17th century and now fills 25 rooms of the castle up to the ceiling with files.